Welcome to Off The Shelf - your weekly supplement for sustainable food. This is a newsletter designed to keep us honest about what we’re putting on our plates. If you like it, please subscribe or share it with a mate!

A few weeks ago, I fessed up to having an extremely sweet tooth. Desserts, chocolate, cakes, biscuits - I’ll sweep them all into my shopping basket if nobody stops me. Which is why I have a vested interest in government policy in this area.

THE BACKGROUND

Obesity is a big problem. It’s been associated with heart disease, diabetes and cancer, as well as mental health issues. 13% of adults worldwide are obese, and obesity was linked to 4.7 million deaths in 2017. In the UK, one fifth of children leaving primary school are obese. This is driven by two potential factors: taking in too many calories, or not expending enough energy. As we can see here, the supply of calories available for consumption across the globe has been steadily increasing for years. And we’re hardly getting more active to offset that, are we?

THE GOVERNMENT TO THE RESCUE

In 2020, the UK government published its anti-obesity strategy. Pundits speculated that this came in large part in response to Boris Johnson’s own brush with death during the early Covid days. Whether that’s true or not, the strategy contained measures to curb the marketing of products high in sugar and salt: for example, banning buy-one-get-one-free deals, and prohibiting advertising of such products on TV before 9pm.

…NOT SO FAST, NANNY

But Liz Truss’s new government recently announced that these measures are on hold, subject to review. And there are two purported reasons for this. The first is that people don’t want ‘nanny state’ policies. During the recent leadership contest, Truss said that people ‘don’t want the government telling them what to eat’. The second reason is that the new government wants to unleash economic growth and ease the cost of living, and thinks that curbs on promotional offers would make it more difficult for families to afford to feed themselves.

TIME FOR SOME COMMON SENSE

The rowback has been met with outrage from campaigners. And I have to say I’m on their side. Using special offers to aggressively market unhealthy foods is only going to lead to more inequality when it comes to health outcomes. If these unhealthy items are the cheapest, they’re going to be bought disproportionately by those least well-off, and those are the people that will ultimately end up at higher risk of the conditions I mentioned earlier, thereby creating further inequality.

It’s also a false economy at a national level: even if the continued promotion of these products does lead to higher economic growth, as the government is suggesting, then what about the additional cost down the line when the NHS has to foot the bill for long-term health conditions? A report in 2017 by Public Health England suggested that the effects of obesity and being overweight could cost almost £50 billion annually by 2050, with the NHS having to cough up £10 billion to deal with the direct impacts. I wonder if Kwasi Karteng thinks that keeping these promotions will net the exchequer quite that much?

THESE POLICIES WORK!

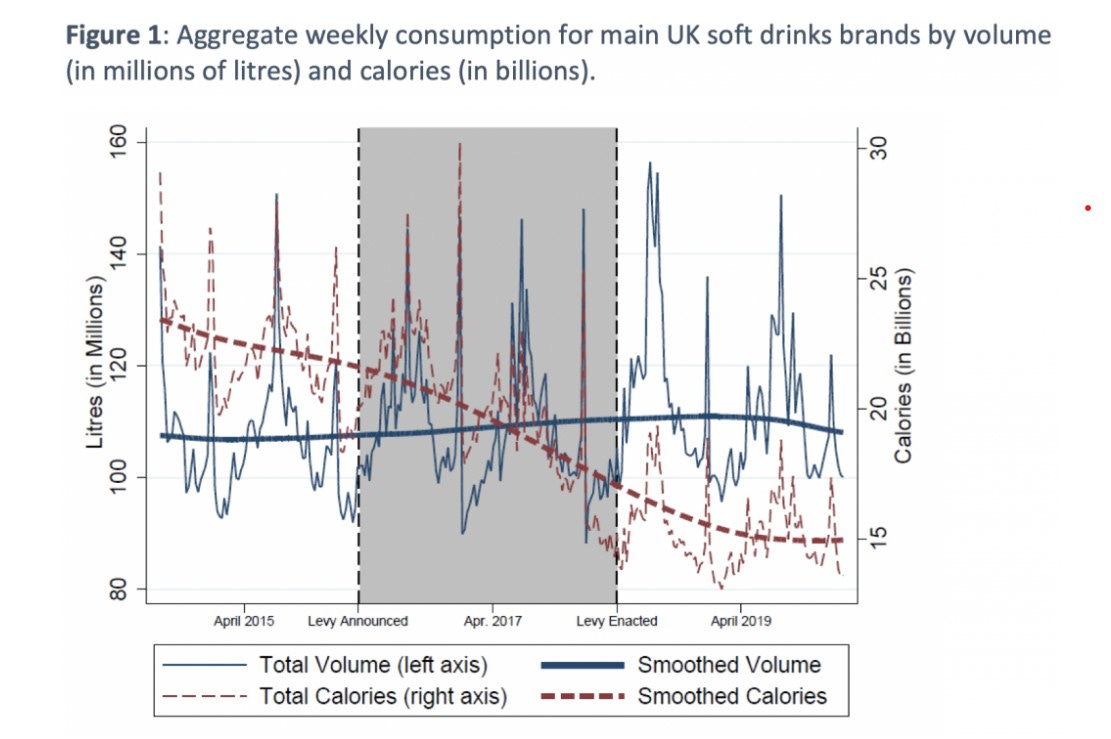

If you want to see what happens when these types of policies are implemented, take a look at this blog, and the chart below. It’s an interesting case study. When the government announced a tax on sugary soft drinks a few years ago, the real effect wasn’t higher consumer prices, or a drop-off in consumption of soft drinks: it was that manufacturers changed the recipes to reduce their sugar content. Aside from a few grumbles (Reddit is great for this stuff, by the way) that Irn Bru didn’t quite taste the same again, these shifts went largely unnoticed by the broader public.

In my view, these policies can be a win-win. People still get to buy the stuff they like, but it’s become a bit less unhealthy. Isn’t that progress?

MORSELS

🪓 Deforestation is accelerating in Brazil

🗳 Food is being used as a bargaining chip in Russia’s sham referendums

Data as of 26 September 2022. Just to keep my senior politician readership out of hot water on Sunday morning TV. Price of milk represented by the average price of comparable 2-pint bottles at 5 major retailers in the United Kingdom (Tesco, Aldi, Sainsbury’s Waitrose and Marks & Spencer). Index is equally weighted and based on online prices. Methodology is purely proprietary and utterly unscientific. For actual price data that might be remotely useful for economic analysis, try the Office for National Statistics.

HOW CAN WE STAY IN TOUCH?

📸 I’m on Instagram where I chronicle my cooking @slothychef

👤 Same deal for Facebook Slothy Chef

📧 Drop me a note by replying to this email.

Somewhat at the other end of the spectrum from the bogof deals you discuss, but I’ve noticed my local supermarket has scaled back the range of organic products they stock in recent weeks. I’m not sure whether this is solely in response to expected consumer appetite given the rising cost of living, but fewer organic options on the shelves can only be a bad thing for sustainable farming and animal welfare?