Photo source: Rodrigo Flores

Back from my lazy week off, and raring to go. What better way to welcome in the shorter days and browning leaves than by introducing your friends to a sweet, slightly spiced, warming cup of Off The Shelf? Like a box of chocolates, there’s something for everyone.

And if you haven’t subscribed yet, go on. You only live once. Just like the fudge in a box of heroes, it’s just too tempting.

I’ve always liked a drink, but I’ve never struggled to cut out booze when I’ve felt like it. I’ve been known to enjoy a flutter on the horses, and I’ve bet disastrously on golf without any interest in the sport whatsoever. But my gambling has never got out of control. I’m also on the verge of a full-blown StarCraft II addiction, yet I still manage to hold down a job and write this newsletter every week, so it hasn’t taken over.

But when it comes to chocolate, things are different. I have a painfully sweet tooth which means I just can’t stop. All kinds of chocolate: biscuits, bars, cakes, pastries. Dark, milk, white, blonde. I’m not ashamed to admit that one of the reasons I married my wife is because of her knack of getting press invitations to the seasonal Hotel Chocolat product launches. Christmas-themed chocolates in July. I don’t care whether they’re reindeer-shaped or not, just give me the goodie bag.

I don’t think I’m alone. As a nation, we eat a lot of the stuff. According to the British Heart Foundation, the average Brit will consume 7,560 chocolate bars, 2,268 slices of chocolate cake and 8,316 chocolate biscuits in a lifetime. I’m probably already there.

I’m not shocking anyone: chocolate is popular. But is it sustainable?

CHOCOLATE HAS AN ENVIRONMENTAL FOOTPRINT…

…which is explained in large part by deforestation. The key ingredient in chocolate is cacao, which grows primarily in humid, equatorial regions. The major producers include Ghana, the Ivory Coast, Indonesia and Brazil. And to feed global demand, this means that space has to be made to grow the stuff, leading to the clearing of land. And in addition, other key ingredients come with their own environmental footprint: palm oil, for example (although consumer patterns are putting manufacturers under pressure to steer clear of that), and milk.

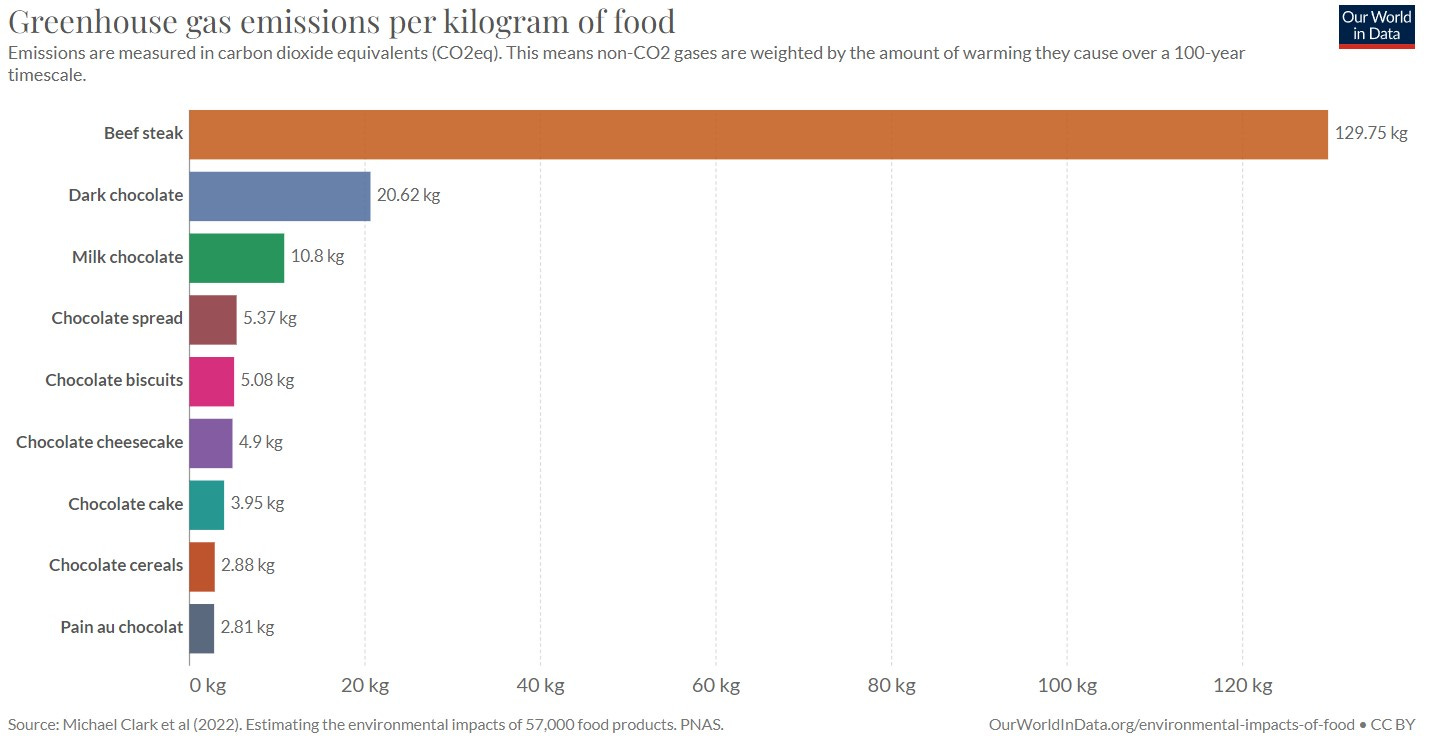

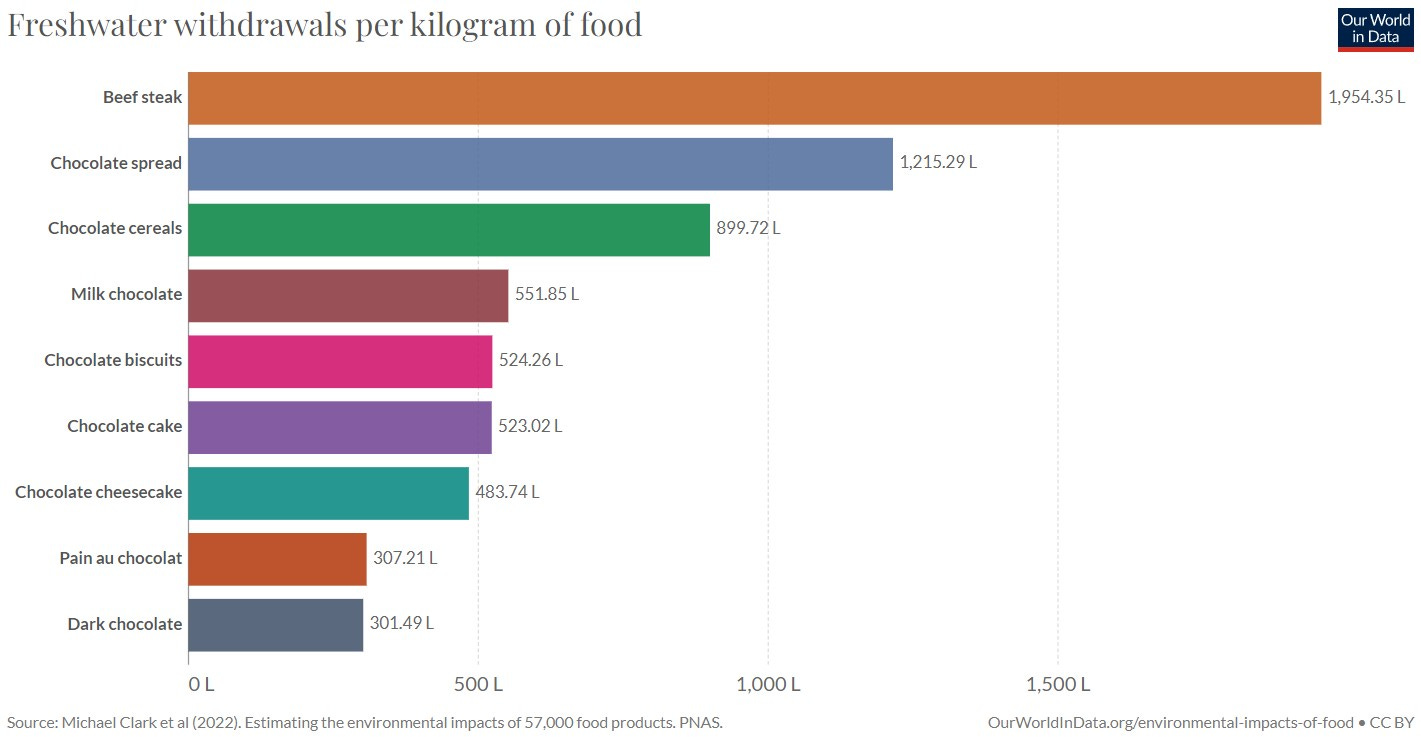

Our World In Data remains my favourite place to start when looking at this stuff. And that tells me that, depending on which metric you’re looking at, the impact of chocolate isn’t negligible. I’ve added some charts at the end of this week’s edition in case you want to take a closer look.

For further reading on the environmental side, I found this quite a helpful summary. There’s also a whole other rabbit hole you can down when it comes to the biodiversity of cocoa beans - start by listening to this podcast.

…BUT IT’S THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROBLEMS THAT REALLY SHOCKED ME

Much of our chocolate comes from slavery and exploitation.

This is hard to hear, but it’s true. Two thirds of global production is focussed in West Africa, particularly Ghana and the Ivory Coast. Here, literacy rates are low, and poverty is rife. Education is unattainable for many, and families are often forced to put their children to work from an early age on the family farm, or send them elsewhere to earn. The conditions in which these children work are appalling, and the pay is terrible. A report in 2015 by the US Labor Department indicated that more than 2 million children were engaged in dangerous work in cocoa-growing regions.

This situation was eloquently exposed a couple of years back by the Washington Post, who sent photographers and reporters to the Ivory Coast to see what was going on. They found that:

The majority of the 2 million child laborers in the cocoa industry are living on their parents’ farms, doing dangerous work such as clearing forests with machetes, carrying heavy sacks around and spraying pesticides. A number of those 2 million children are trafficked from other countries.

Traffickers offer money or other incentives to families from surrounding countries to travel to Ivory Coast. About half of those interviewed in a survey said they were not free to return home, and the majority had experienced physical violence or threats. Some were never paid.

Farmers on cocoa plantations are paid as little as $9 per week, with their labourers in turn paid about half of that. Children on one farm were being paid about 85 cents a day. This is well below the extreme poverty line.

An agreement was been made by the world’s big chocolate companies to to eradicate child labour from their supply chains and to develop ‘standards of public certification’ which would indicate that cocoa products had been produced ‘without any of the worst forms of child labour’. But these companies have missed successive deadlines to make progress, and haven’t been held to account.

The Ivory Coast has passed laws which define and penalise child labour. The government has also built schools in rural areas and cracked down on child trafficking. But it’s flourished anyway because of the country’s inability to enforce these laws.

It’s therefore likely that much of the chocolate we’re buying relies in some way on child labour, which remains widespread.

WHAT’S BEING DONE ABOUT THIS?

Unfortunately, this is a multi-faceted problem which can’t just be solved overnight. There’s a huge global market for chocolate, which means that cocoa is a commodity in perennial demand, and labour is needed for its production and distribution. And since it grows primarily in a poor region with high levels of corruption, as well as limited education opportunities, the potential for exploitation is high. This will be a problem until the root causes of poverty are addressed.

However, awareness of the problem is growing, and moves are underway to mitigate it:

Nonprofit groups — such as Fairtrade, and Rainforest Alliance — provide a valuable voice when it comes to protecting growers, and have developed labels for products which have been produced according to ethical standards. The idea is that greater transparency will lead to higher standards at all stages of the supply chain. Products with a Fairtrade label provide a level of assurance that growers will receive a premium on top of their usual wage. It certainly seems like a sensible start: look out for labels like this on your chocolate bars. Labels don’t solve everything, though, and there are practical limitations: for example, the premium provided to farmers is only 10% - not much for the person earning 85 cents a day. In addition, cocoa farm inspections are sporadic, with fewer than 1 in 10 farms inspected each year, and they’re announced in advance, so it’s fairly easy for offenders to avoid scrutiny altogether. Obviously, we’re going to need more than certification.

And that’s where the big industry players come in. It’s easy to bash ‘big chocolate’, and assume that they’re the bad guys. Interestingly, as I was inspecting the confectionary aisle this week, I had a look whether Cadburys bars carried a fair trade label. I was encouraged to see a green ‘Cocoa Life’ label, with a bold statement about ‘100% sustainably-sourced cocoa’. On closer inspection, I learned that Cocoa Life is the sustainable cocoa program for Mondelez International, which owns Cadburys. So this label is, if we’re being uncharitable, a case of a big company marking its own homework. Nevertheless, the initiatives being developed under such programs can only be a good thing - other big companies have similar programs - and it does suggest that the industry is moving in the right direction, albeit slowly.

Some companies go further, and have modelled their entire brand around eliminating slavery. One of the big emerging brands is Dutch company Tony’s Chocolonely, founded by a journalist who was appalled by the extent of child labour in the chocolate industry. It has committed, with a 3-pillar roadmap (I wonder which trailblazing consultant suggested a 3-pillar roadmap) to make “100% slave-free chocolate the norm”. If you’ve enjoyed one of Tony’s bars, have you ever wondered why they’re pre-scored into uneven pieces? Well… it symbolises the inequality in the chocolate industry. Don’t say I never teach you anything. Tony commits to paying farmers a higher premium than other manufacturers - which explains why it’s more expensive when it hits our shelves. Personally, I love their products (the orange coloured sea salt one in particular) and it’s not actually that much more expensive than Cadburys when you look at it by weight (Tony’s bars are a similar size in surface area, but much heavier). Before we assume that this is the silver bullet, be aware the company has had its share of controversy. Slave Free Chocolate, a pressure group, dropped it from its list of ethical producers after allegations of involvement with a company being sued in America by former child-workers in Ivory Coast. That case has since been thrown out by the Supreme Court, but it shows that even the good guys in the industry can be implicated by association in a complex supply chain.

There’s no single solution to all of this. It’s going to need active engagement from the big producers, under the watchful eye of independent parties who have developed internationally-recognised certification. And ultimately, it’s an economic story: the root of all this is poverty, and so until the contributing factors to that have been addressed, we’re unlikely to see a huge change.

WHAT CAN WE DO AS CONSUMERS?

Cutting out chocolate altogether might be the simple solution. But 1) good luck with that, and 2) I’m not sure this would alleviate poverty and exploitation in the growing regions, given that cocoa is one of the key industries in which so many people work.

Instead, I think we need to be more conscious about which products we’re buying, and start to ask more questions about the supply chains of the companies making those products. Look for the Fairtrade label, or peruse lists of ethical producers, and try to get a feel for how the product has been made.

Granted, it’s tough to distinguish between marketing mumbo-jumbo and genuine action, but collective consumer behaviour is powerful: the more companies see that their customers care about an issue, the more resources they will put into addressing it.

Which ethical chocolate brands haven’t I mentioned? Let us know in the comments so we can all go and gorge on them.

CHOCOLATE IN CHARTS - THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

Data as of 4 September 2022. Price of milk represented by the average price of comparable 2-pint bottles at 5 major retailers in the United Kingdom (Tesco, Aldi, Sainsbury’s Waitrose and Marks & Spencer). Index is equally weighted and based on online prices. Methodology is purely proprietary and utterly unscientific. For actual price data that might be remotely useful for economic analysis, try the Office for National Statistics.

HOW CAN WE STAY IN TOUCH?

📸 I’m on Instagram where I chronicle my cooking @slothychef

👤 Same deal for Facebook Slothy Chef

📧 Drop me a note at info@slothychef.co.uk

GROWING OUR COMMUNITY

I’ve got big ideas about building a community around this subject. I hope you can get involved. It’s easy - you can start by sharing across your networks using the button below.

Thanks for this Liam - this has really given me things to think about. A pledge to make chocolate ‘without any of *the worst forms* of child labour’ seem a really, pathetically low bar.

Brilliant work, Liam, I think this is my favourite post of yours so far. (I'm now thinking I should rethink my favourite brands too)